Big-O Explained and Why You Will Never Beat a Pigeon

In this blog post I will prove you will never be able to write an algorithm that scales better than a pigeon and also teach you some basic concepts when it comes to Big O notation.

Big O is often ignored by self-taught programmers and often forgot by computer science students after they graduate, but it is actually very important, not only for being approved in job interviews and nailing those whiteboard exercises but also for your day-to-day job.

It is really important for programmers to be able to design efficient algorithms and it is even more important for them to be able to compare them to others and do the optimal choice based on facts and mathematical proof.

After all, as the first of Akin’s Laws of Spacecraft Design states:

Engineering is done with numbers. Analysis without numbers is only an opinion.

Let’s ignore the hottest frameworks and tools for a while and dive deep into some good and old mathematics.

What is Big O notation?

Big O notation is a mathematical way of describing how well algorithms scale and perform given a certain input.

Big O is determined in terms of the size of an input.

Let’s say we have a randomly generated Array with n elements and we want to find the index of a specific value in it.

We would probably write a code that looks like this:

function find(arr, val) {

for (let i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) {

if (arr[i] === val) {

return i

}

}

return -1

}

In order to determine the Big O classification of our find function, we need to determine how many iterations it would need for each input size. This is also known as an algorithm’s time complexity.

When we talk about Big O we are interested in the worst case possible. We don’t want to rely on luck. Due to this, even though it is possible that we find the element we are looking for on the first index, we will only consider the case when we need to go through the whole Array to find it.

For 10 elements we need 10 iterations, for 20 we need 20 iterations and so on. Now, if we consider the length of our array (the size of our input) to be n, then we need n iterations to get what we want and therefore we can say that this algorithm’s complexity is O(n).

If we’ve had an algorithm that needs to count the number of duplicate elements in an array and we wrote it like this:

const arr = [2, 4, 1, 5, 2, 5, 1]

function countDuplicates(a) {

let duplicates = 0

for (let i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

for (let j = 0; j < a.length; j++) {

if (a[i] === j[i]) {

duplicates++

}

}

}

}

Now, the complexity of countDuplicates is N^2, because for each item in arr we need to go through all the other items, which makes us iterate in it N * N times.

Your best complexity ever can only be O(1) which happens when you alway need to take a single action doesn’t matter how big the input size is. If you have an array which contains a series of sequential whole numbers starting at 1 and you wanted to write a function that told you the sum of all of them you could write a function like this one:

const seqNumbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

function seqSum(seqArr) {

const n = seqArray.length

return n * (n + 1) / 2

}

Since we are always doing one iteration and it’s based on the array’s length so that we don’t have to iterate through all of its elements, it will perform the same for every array of sequential numbers, doesn’t matter how big it is. And this is why this kind of algorithm is said to have constant complexity.

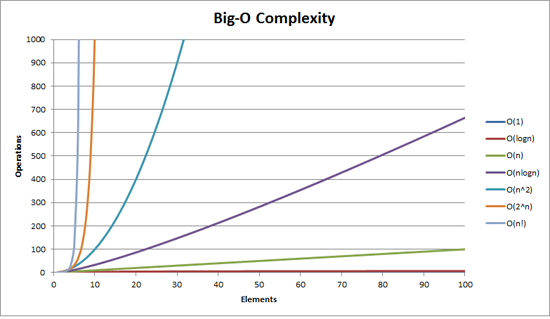

Here are some of the most well-known complexity descriptions:

- O(1) - Constant - When we have a constant amount of iterations doesn’t matter the size of an input.

- O(log N) - Logarithmic - When the number of remaining iterations drops by half in each iteration

- O(N) - Linear - When we need to go through the whole input once.

- O(N log N) - Linearithmic - When we need to iterate N times but in each of these iterations the number of iterations left drops by half (i.e.

MergeSort) - O(N^2) - Quadratic - When we need to go through the whole input for each item in it

And this is an awesome graph I’ve found in this StackOverflow question, which demonstrates the complexity of the items above:

Constants and Growth Rates

Now let’s take some time to improve the second algorithm above by using an object in order to avoid having N^2 complexity.

const arr = [2, 4, 1, 5, 2, 5, 1]

function countDuplicates(a) {

let duplicateMap = {}

for (let i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

let n = duplicateMap[a[i]] || 0

duplicateMap[a[i]] = n + 1

}

return Object.keys(duplicateMap).filter(numberKey => duplicateMap[numberKey] > 1)

}

Now, instead of having O(N^2) complexity, we’ve got O(N) complexity.

But wait, don’t we have to go through the array twice? Wouldn’t its complexity be O(2N)?

Actually not, because when dealing with Big-O we always drop constants and that happens because we’re interested in growth rates, not absolute values.

If we had an algorithm that does 2N operations versus one that does N operations, they would scale the same. Suppose you’ve got an input with 100 items and one with 500 items, these would be your results:

- For

N:- 100 items = 100 operations

- 500 items = 500 operations

- For

2N:- 100 items = 200 operations

- 500 items = 1000 operations

As you can see, as you multiply the size of the input by 5, the number of operations also increases by 5 times, it does not matter if you’re dealing with 2N or N.

To sum it up, here goes an excellent answer by templatetypedef on StackOverflow:

Big-O notation doesn’t care about constants because big-O notation only describes the long-term growth rate of functions, rather than their absolute magnitudes. Multiplying a function by a constant only influences its growth rate by a constant amount, so linear functions still grow linearly, logarithmic functions still grow logarithmically, exponential functions still grow exponentially, etc. Since these categories aren’t affected by constants, it doesn’t matter that we drop the constants.

In the real world, however, these constants do matter in terms of time, what I’m trying to say is that when it comes to Big-O we’re more concerned with growth rates and not absolute time values.

If you had an algorithm that took 100ms for each operation, you’d cut its overall running time by half if you went from 2N to N, because then, for an input with 1000 items you’d be doing 1000 operations instead of 2000 and therefore your algorithm would run in ~1 second instead of ~2 seconds.

Why You Will Never Beat a Pigeon

If, instead of running an algorithm, you could simply ask a pigeon to go from point A to point B and bring a USB stick with the answer, it would be better or at least as efficient as any algorithm you will ever write.

This happens because it doesn’t matter the size of the data you are dealing with, the pigeon will always fly from point A to point B in the same amount of time, which makes it have a complexity of O(1).

This is a real experiment made by a South African company called “The Unlimited” and you can read more about in this excellent Quora Answer by Gayle Laakmann McDowell.

Get in touch!

If you have any doubts, thoughts or if you disagree with anything I’ve written, please share it with me in the comments below or reach me at @thewizardlucas on twitter. I’d love to hear what you have to say.

Thanks for reading!